The Scottish writer John McNeillie, who died on 24 June 2002, aged 85, left a legacy of over forty books, among them a number of minor classics, and several decades of weekly nature journalism in the pages of the dentists’ favourite sedative, Country Life for which he wrote under the pen name Ian Niall. Not only did McNeillie possess the eye and ear of a poet, he could also tell a spell-binding story.

The Scottish writer John McNeillie, who died on 24 June 2002, aged 85, left a legacy of over forty books, among them a number of minor classics, and several decades of weekly nature journalism in the pages of the dentists’ favourite sedative, Country Life for which he wrote under the pen name Ian Niall. Not only did McNeillie possess the eye and ear of a poet, he could also tell a spell-binding story.

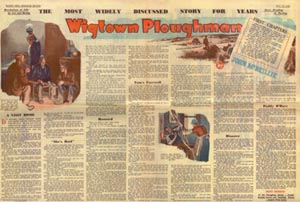

If the natural history essay was his true métier, as found in such volumes as The Poacher’s Handbook (1950), Trout from the Hills (1961), and his memoir A Galloway Childhood (1967), as well as several other collections, dramatic realist fictions also featured in his output and were where he first made his mark. John McNeillie’s first book, Wigtown Ploughman: Part of His Life, was published by the London firm  of Putnam &Co, in March 1939. Its author was then twenty-two. Serialised in Glasgow’s Sunday Mail, the book caused a furore with its account of the impoverished lives and of what was seen as the ‘immorality’ of the cotters in the Machars of Wigtownshire. The book (in print in Scotland today and essential reading for all Gallovidians) played a key part in the instigation of housing reforms in the region. Hugh Walpole, writing in the Daily Sketch, though disturbed by its violence none the less found Wigtown Ploughman ‘shot through with beauty’ and praised and envied its authenticity. Other reviewers noted this quality, and some saw it as ‘equally authentic’ with the work of Lewis Grassic Gibbon, who had died in 1935.

of Putnam &Co, in March 1939. Its author was then twenty-two. Serialised in Glasgow’s Sunday Mail, the book caused a furore with its account of the impoverished lives and of what was seen as the ‘immorality’ of the cotters in the Machars of Wigtownshire. The book (in print in Scotland today and essential reading for all Gallovidians) played a key part in the instigation of housing reforms in the region. Hugh Walpole, writing in the Daily Sketch, though disturbed by its violence none the less found Wigtown Ploughman ‘shot through with beauty’ and praised and envied its authenticity. Other reviewers noted this quality, and some saw it as ‘equally authentic’ with the work of Lewis Grassic Gibbon, who had died in 1935.

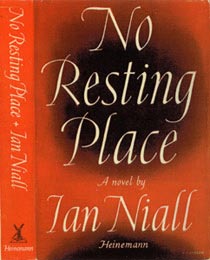

McNeillie’s controversial debut was followed by Glasgow Keelie, April 1940, a story of young hooligans in Glasgow in which Hollywood and the gangster movie play a vital role. McNeillie had a cinematic eye and ear and this book was a film just waiting (in this case, in vain) to me made. A second agricultural novel Morryharn Farm, followed in January 1941. But by now the war gave the world other things to think about. McNeillie spent the duration working in a precision tool engineering works in North Wales and there he would settle to live for more than forty years, finding Wales and the Welsh people deeply congenial. A fourth novel No Resting Place proved too violent in its telling for Putnam, but it was seized on eagerly by Heinemann and appeared in 1948, as a first novel by Ian Niall. McNeillie’s second debut proved no less remarkable than his first. Set in southwest Scotland, though the location isn’t precisely disclosed, No Resting Place relates the fortunes, feuds and misfortunes of the Kyle family, a tribe of ‘tinkers’.

McNeillie’s controversial debut was followed by Glasgow Keelie, April 1940, a story of young hooligans in Glasgow in which Hollywood and the gangster movie play a vital role. McNeillie had a cinematic eye and ear and this book was a film just waiting (in this case, in vain) to me made. A second agricultural novel Morryharn Farm, followed in January 1941. But by now the war gave the world other things to think about. McNeillie spent the duration working in a precision tool engineering works in North Wales and there he would settle to live for more than forty years, finding Wales and the Welsh people deeply congenial. A fourth novel No Resting Place proved too violent in its telling for Putnam, but it was seized on eagerly by Heinemann and appeared in 1948, as a first novel by Ian Niall. McNeillie’s second debut proved no less remarkable than his first. Set in southwest Scotland, though the location isn’t precisely disclosed, No Resting Place relates the fortunes, feuds and misfortunes of the Kyle family, a tribe of ‘tinkers’.

The documentarist Paul Rotha took the book up and filmed a treatment of it, in Co. Wicklow, with Michael Gough in the key role and a cast of Abbey Players, including Jack MacGowran, Noel Purcell, Eithne Dunne, Maureen O’Sullivan, and Diana Campbell in support. The film, released in 1952, is a classic of Irish cinema. A smattering of Irish was interpolated into the script, which otherwise draws much of its dialogue verbatim from the novel itself. It was shot on location around Enniskerry village, Glencullan and Kiltiernan, and went from Wicklow to the Venice film festival. There it took the attention of among others Winston Churchill, who, patriotically perhaps, told the Daily Mail it was his favourite movie at the festival that year. The film fell a casualty to what Rotha would lament as the politics of the British film industry and never enjoyed general distribution. A showing, in May 2001, at the Irish Film Centre in Temple Bar, Dublin, drew a considerable audience, among them representatives of traveller communities, for whom the film gives the first ever unsentimental cinematic account of their way of life, told from their side of the story.

The documentarist Paul Rotha took the book up and filmed a treatment of it, in Co. Wicklow, with Michael Gough in the key role and a cast of Abbey Players, including Jack MacGowran, Noel Purcell, Eithne Dunne, Maureen O’Sullivan, and Diana Campbell in support. The film, released in 1952, is a classic of Irish cinema. A smattering of Irish was interpolated into the script, which otherwise draws much of its dialogue verbatim from the novel itself. It was shot on location around Enniskerry village, Glencullan and Kiltiernan, and went from Wicklow to the Venice film festival. There it took the attention of among others Winston Churchill, who, patriotically perhaps, told the Daily Mail it was his favourite movie at the festival that year. The film fell a casualty to what Rotha would lament as the politics of the British film industry and never enjoyed general distribution. A showing, in May 2001, at the Irish Film Centre in Temple Bar, Dublin, drew a considerable audience, among them representatives of traveller communities, for whom the film gives the first ever unsentimental cinematic account of their way of life, told from their side of the story.

There was a strongly reclusive and self-effacing element in John McNeillie’s character and the acquisition of a pen-name came to suit him well. He can scarcely be said ever to have made much attempt to promote himself or his work. During the 1950s and 1960s he wrote not only for Country Life but also at the same time contributed to the Spectator. In this period he also edited for IPC magazines the fishing monthly Angling, all from a small semi-detached house off the Abergele Road in Old Colwyn while holding down a full-time job at the Ratcliffe Tool Company. He was a passionate fly fisherman.

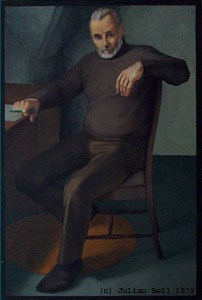

Born in Old Kilpatrick, Dalmuir, on 7 November 1916, John Kincaid McNeillie was the eldest son of Robert McNeillie and of Jean McDougall. Robert McNeillie, a blacksmith’s son from Garlieston in Wigtownshire, was then an apprentice engine fitter working on Clydeside for the firm of Beardsmore. His wife Jean was a daughter of John McDougall, a steward with the Cunard line and of a Gaelic-speaking mother, Ellen Munro. (She was an aunt of Neil Munro, the Glasgow journalist and author of The Lost Pibroch and of the ‘Para Handy’ stories, as recently retold for television.) At some point, when he was a little short of three years old, during an outbreak in Glasgow of menigitis, in which his younger sister fell a fatal victim, the infant McNeillie was despatched to Galloway to be cared for by his paternal grandparents John and Elizabeth McNeillie, then tenants of the Vans Agnew family of Barnbarroch, at North Clutag farm. It was in this horse-drawn time-warp, closer to the world of Robert Burns both in speech and custom than to the twentieth-century, that McNeillie spent a profoundly affecting part of his childhood. It was a world and time he would never escape, an Eden that formed the backdrop to almost all he wrote, and almost all he cared dearly to talk about. John McNeillie was made a Doctor of Letters by Glasgow University, for his contribution to Scottish literature, in 1998. He leaves a wife, Sheila, and a daughter and two sons. There is a portrait of him by the painter Julian Bell, in the family’s possession.

Born in Old Kilpatrick, Dalmuir, on 7 November 1916, John Kincaid McNeillie was the eldest son of Robert McNeillie and of Jean McDougall. Robert McNeillie, a blacksmith’s son from Garlieston in Wigtownshire, was then an apprentice engine fitter working on Clydeside for the firm of Beardsmore. His wife Jean was a daughter of John McDougall, a steward with the Cunard line and of a Gaelic-speaking mother, Ellen Munro. (She was an aunt of Neil Munro, the Glasgow journalist and author of The Lost Pibroch and of the ‘Para Handy’ stories, as recently retold for television.) At some point, when he was a little short of three years old, during an outbreak in Glasgow of menigitis, in which his younger sister fell a fatal victim, the infant McNeillie was despatched to Galloway to be cared for by his paternal grandparents John and Elizabeth McNeillie, then tenants of the Vans Agnew family of Barnbarroch, at North Clutag farm. It was in this horse-drawn time-warp, closer to the world of Robert Burns both in speech and custom than to the twentieth-century, that McNeillie spent a profoundly affecting part of his childhood. It was a world and time he would never escape, an Eden that formed the backdrop to almost all he wrote, and almost all he cared dearly to talk about. John McNeillie was made a Doctor of Letters by Glasgow University, for his contribution to Scottish literature, in 1998. He leaves a wife, Sheila, and a daughter and two sons. There is a portrait of him by the painter Julian Bell, in the family’s possession.

Since his death he has been honoured by the naming of the John McNeillie Library in the former county buildings at Wigtown, on which same square may be found The Wigtown Ploughman Hotel; and by the inauguration, as part of the Wigtown Literary Festival, of the Annual John McNeillie Lecture.

For further information, see the links below:

Comments regarding John McNeillie’s work

A Note on John McNeillie’s First Publisher

Note On Previous Dust-Jackets And Illustrator

© Andrew McNeillie 2004