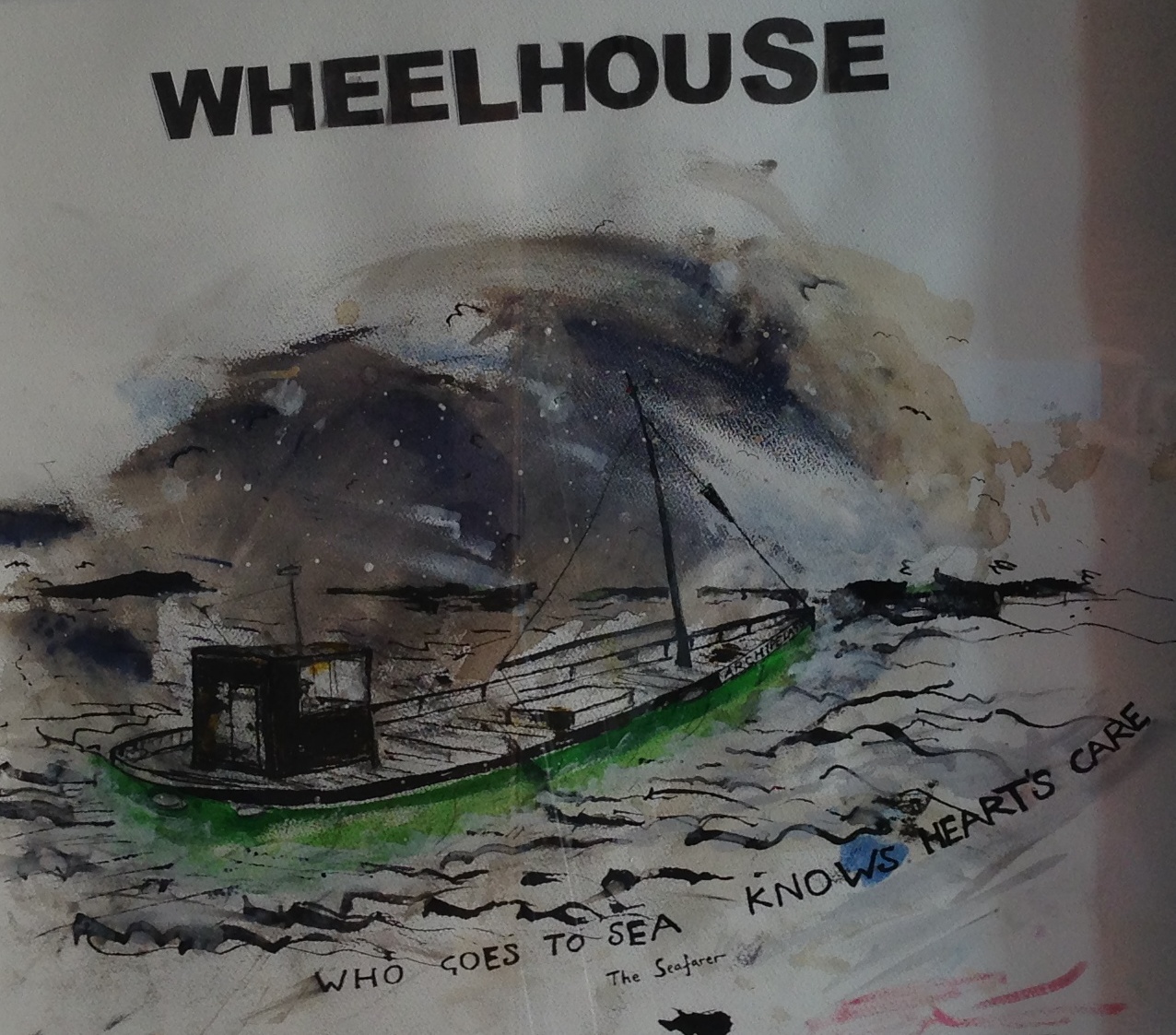

Who goes to sea knows heart’s care.

Groves blossom burghs grow fair

meadows beautiful. World quickens.

All things urge spirit to embark

fare far by flood-ways

though melancholy call of summer’s lord

the cuckoo bode bitter heart-sorrow.

from ‘In the Wake of the Seafarer’ Winter Moorings (2014)

Welcome to the wheelhouse!

The big news: Archipelago has acquired a second fishing boat, a single rig prawn trawler we’re in the process of converting into a back-up floating editorial office: ARCHIPELAGO II. See the picture ‘Northwest Passage’ below: Skipper Macdonald Lockhart at the wheel, Katherine Rundell in charge of tightropes. Both images are by Andrew McNeillie.

The blog that follows on from the ‘Northwest Passage’ image, about a visit to St Kilda, is by George Thomas and by Gordon Campbell. Click play to hear George Thomas soloing with his song of the Solon, first performed in public here.

A Journey to St Kilda

Why was our journey to St Kilda so moving for me? Setting aside the build-up, the reading, the companionship in endeavour and the disappointment of failing in the first attempt there are a number of lifelong themes that help me explain or, at least, rationalise my pleasure in the journey. G. K. Chesterton considered ‘Over the hills and far away’ to be among the most beautiful lines in English poetry. It evokes a dim landscape beyond the horizon where untold adventures and new experiences await. It also suggests wildness, an atmosphere beyond the realms of civilisation and everyday thinking. I’ve been sensitive to this magic from an early age. As a teenager I loved hitchhiking to other places, walking along roads through new countryside, talking to strangers and just ‘getting by’. St Kilda is a sort of Ultima Thule in this regard.

As a second theme, I’ve always been held in thrall by redundancy in a historical sense and images of human experience that are vivid, passionate and now quite beyond reach. Of course, this is true of history in general but has been emphasised for me in particular ways. As a young boy, I loved football and supported Crewe Alexandra. Researching the history of the side, I discovered that it was formed from a cricket club in 1877. Considering these distant matches, I also became interested in the fate of another northern team, Accrington Stanley. This faraway side has something in common with St Kilda: frustrated hopes and dreams, exhausted passion, an unfeasible way of life and, eventually, abandonment and evacuation.

If Accrington Stanley has made something of a comeback in recent years, as I believe it has, then so also has St Kilda, with its double World Heritage status, military significance and resident groups of volunteers. You can stay in The Street now, although there are no longer gannet guts on the floors. Soay sheep still roam the island, with fleece like dreadlocks.

A third theme in my journey towards St Kilda was a gift subscription to the National Geographic, generously awarded one Christmas by my Great Aunt Eva, a splendid woman who took mustard with every meal, even fish. I loved the arrival of the bright yellow packages all the way from the USA, with their contents of brilliantly exotic photos, colourful map supplements and adverts for Chevrolet Impalas and colour television sets. They set me off on a course of social anthropology and a hunger to explore the far flung places in the world which, sadly, fifty years later I have barely begun to do.

Small communities with their custom and practice are interesting in themselves but so too are their links with neighbours. St Kildans appeared remote, primitive and stupid to many Victorian (and later) visitors but the most perceptive writers emphasise their links with neighbouring Harris and Skye, fifty miles or so across the Atlantic. The network of survival, trade, belief and cultural shift is endlessly fascinating.

The history of St Kilda reminds us of the ever present closeness of tragedy. Here is a retelling in song of a story from Martin Martin, when men were out taking birds from Boreray when their boat, the only one on St Kilda, was lost and they had to wait eight long weeks for rescue.

To return to poetry, there are the names Dun, Hirta, Boreray and Soay; the fact that there is no St Kilda – perhaps the name results from an error of correction as far back as the 16th century. The physical prowess of the vanished men, suspended on ropes of hair, hemp and leather on all but impossible cliffs, risking fall and the stabbing gannet’s bill for eggs and young birds is simply heroic. The cold, cruel sea, the topography of Hirta, one face amphitheatre and the other cliff, and the sheer difficulty of reaching the place makes it a certain goal for me. I hope one day to return for a longer stay.

George Thomas

The same Journey to St Kilda

We began a year ago, tourists pretending to be travellers. The weather was bad, and we sat in a hotel bar in Tairbeart/ Tarbert (Harris), hoping that the seas would calm to the point at which a visit to St Kilda would be viable. In the end, our time ran out, and we retreated, determined to return. A year later, we again assembled in Tairbeart, and this time our determination made our intention feel like a pilgrimage, or even a mission. Our group of seven consisted of three special needs teachers, a PR consultant, an oil executive, a musician and a pedant; our poet, Andrew McNeillie, had been unable to join us on this second attempt, so there could be no companion poem to ‘On Not Sailing to St Kilda’, which Andrew included in his Clutag blog ‘Weather Not Permitting’ of 2 June 2013 (scroll down to see).

This was in a sense a very literary voyage, in part because of the scale of writing about St Kilda, which began with Martin Martin’s A Late Voyage to St Kilda (1698) and now amounts to scores of books and hundreds of articles. In recent years there have been wrangles about the historiography of St Kilda, which was long presented as a story of romantic isolation that ended in the inevitable tragedy of evacuation, but it is increasingly seen, thanks in large part to Andrew Fleming’s St Kilda and the Wider World, as an integrated part of the Hebridean communities of the MacLeod fiefdom.

The journey to St Kilda is fraught with uncertainty because of the weather. The climate is hostile, and there are gales for some 75 days a year. We were prepared for a difficult journey, perhaps in the style of Shackleton and his companions crossing in the James Caird from Elephant Island to South Georgia. This was to be an epic journey, one to be enshrined in our memoirs and recounted with ever-increasing exaggeration to our grandchildren. In the event, the sun shone, the sea was as flat as the proverbial millpond, and in place of the James Caird we travelled in Angus Campbell’s turbo-charged catamaran, which had been designed for servicing off-shore wind turbines and so gleamed with high-tech equipment fit to make the boat secure in all weather. We struggled in vain to be uncomfortable.

The emotional effect of our entry into Village Bay was soon abated by the need to lower ourselves into inflatable boats for the thirty-second journey to the shore. The use of these boats is a precaution directed against rats, whose presence on the island could be ruinous to the birds. We walked from the pier to the island’s army base. Civilian contractors (not soldiers) maintain a radar tracking station, and also provide support for the National Trust for Scotland in the form of communications, electricity, water, medical facilities, helicopter transport and winter cover. Gratitude for these services must be balanced against the ugliness of the base’s buildings, one of which (a washhouse) has been plonked directly in front of the historic Factor’s House.

The base contains a canteen and bar known the Puff Inn, but a history of unhappy incidents and the threat of an al-Qaeda attack on St Kilda mean that the Puff Inn is now off-limits to visitors; one cannot be too careful about seasick terrorists in rowboats.

The village is a ghostly reminder of a community that existed, perhaps continuously, for millennia. The National Trust for Scotland has restored six of the Victorian houses – five for accommodation and stores, and one open to the public as a museum – but none of the older blackhouses between the cottages. The Victorian church and adjoining schoolroom have also been restored, and now stand as mute reminders of the attempts of mainland institutions to bring the St Kildans into line with head office thinking. There was of course resistance, and in the eighteenth century the minster had to pay the islanders to borrow the time of their children in order to teach them to read. After all, reading was of little use to those destined to a life centred on the climbing of bird-cliffs.

Looking at the village through the lens of our reading was a strange experience, as what is visible is the top layer of a complex palimpsest. Glimpses of the layer below the Victorian village can be seen in the ruined blackhouses and in the scanty remains of earlier structures, but much of the early history is invisible. Beyond the confines of the village, one can see many of the 1260 cleits scattered all over the islands. These were formerly used for storing dead seabirds, eggs, feathers, crops and peat, and now accommodate Storm and Leach’s petrels.

The urge to climb beyond the village need not be resisted, and so we set off to climb Mullach Sgar. The sense that the walk would resemble Shackleton’s trek across South Georgia was muted by the ease of the climb (much of it on a military road), the warm sunshine and the laughter. As we climbed we saw ravens, hooded crows, wheatears, and pipits, and on the shore we noticed eider ducks and oystercatchers, but the St Kilda wren eluded our gaze, as indeed did the St Kilda field mouse. There were, however, plenty of Soay sheep, a much-studied breed that descends from the feral sheep that once lived on the nearby island of Soay. Their appeal to the imagination lies partly in the link that they provide to the Faroes, where their genetically-linked cousins lived on the island of Litla Dumun until they were all shot in the 1860s.

At the end of our visit, we returned to our catamaran and travelled to the sea-cliffs. There are more than a million seabirds, and we seemed to see most of them. The cliffs swarmed with gannets (the largest of the world’s forty-four colonies), fulmars, guillemots, razorbills, shearwaters, petrels, kittiwakes and great skuas, and there were puffins in the waters below. These sea-cliffs, the highest in the archipelago, are one of the world’s great sights.

We returned to Harris in our comfortable catamaran, cradling tea and then whisky, stopping only to admire a Risso’s dolphin. We had embarked as pilgrims, but returned as day-trippers.

Gordon Campbell

27 July 2014

[…] McNeillie, excerpt from In the Wake of ‘The Seafarer’ / […]